The Dust Bowl, Its Causes, Impact, With a Timeline and Map

The Dust Bowl was a natural disaster that devastated the Midwest in the 1930s. It was the worst drought in North America in 1,000 years. Unsustainable farming practices worsened the drought’s effect, killing the crops that kept the soil in place. When winds blew, they raised enormous clouds of dust. It deposited mounds of dirt on everything, even covering houses. Dust suffocated livestock and caused pneumonia in children. At its worst, the storm blew dust to Washington, D.C.

The drought and dust destroyed a large part of U.S. agricultural production. The Dust Bowl made the Great Depression even worse.

Key Takeaways

- The Dust Bowl worsened the Great Depression by wreaking havoc on U.S. agriculture and livestock

- Severe drought and bad farming procedures eroded the topsoil

- The Great Plains could turn into a Dust Bowl again if the Ogallala Aquifer is drained dry

Causes

In 1930, weather patterns shifted over the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.1 The Pacific grew cooler than normal and the Atlantic warmer.

The combination weakened and changed the direction of the jet stream. That air current carries moisture from the Gulf of Mexico up toward the Great Plains. It then dumps rain when it reaches the Rockies. This combination also creates tornadoes. When the jet stream moved south, the rain never reached the Great Plains.

Tall prairie grass once protected the topsoil of the Midwest.

Once farmers settled the prairies, they plowed over 5.2 million acres of the deep-rooted grass. Years of over-cultivation meant the soil lost its richness. When the drought killed off the crops, high winds blew away the remaining topsoil. Parts of the Midwest still have not recovered.

As the dust storms grew, they intensified the drought. The airborne dust particles reflected some sunlight back into space before it could reach the earth. As a result, the land cooled. As temperatures dropped, so did the amount of evaporation. The clouds never received enough moisture to create rain.

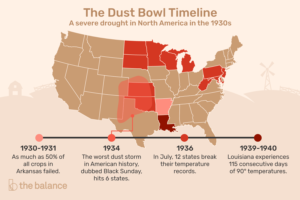

Timeline

The Dust Bowl affected the entire Midwest. The Oklahoma panhandle was hit the worst. It also devastated the northern two-thirds of the Texas panhandle. It reached the northeastern part of New Mexico, most of southeastern Colorado, and the western third of Kansas.7 It covered 100 million acres in an area that was 500 miles by 300 miles.

There were four waves of droughts, one right after another. They occurred in 1930-1931, 1934, 1936, and 1939-1940, but it felt like one long drought. The affected regions could not recover before the next one hit.

1930-1931:

The first drought ravaged 23 states in the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys. It reached as far east as the mid-Atlantic region and hit eight Southern states. Deflation during the Depression drove cotton prices down from $0.18 per pound in 1928 to $0.06 per pound in 1931.11 It cost farmers more to plant cotton than they could get selling it. Farmers could not produce enough food to eat.

President Herbert Hoover did not want the federal government to help.

Instead, Hoover created the National Drought Relief Committee to coordinate nonprofit resources.13 The Red Cross distributed surplus wheat and cotton to drought victims. It supplied $5 million to plant seeds.15 Hoover, as head of the Red Cross, organized a successful $10 million fundraising campaign.1617

1934

This was the hottest year on record until 1998. The 1934 drought led, the following year, to “Black Sunday,” the worst storm of the Dust Bowl, on April 14, 1935.

The drought caused 46.6 million acres of crops to fail in 1935. Over 130 counties lost more than half of their planted acreage.11 Between 1933 and 1934, almost one in 20 farmers were forced to lose their property.

On April 27, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Soil Conservation Act to help farmers learn how to plant in a more sustainable way.

1936

The drought returned with the hottest summer on record.22 It also was the deadliest heatwave in U.S. history with 5,000 fatalities.23

In June, 13 states experienced record temperatures of 110 degrees or higher: Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Texas, Missouri, Indiana, South Dakota, Montana, Mississippi, and Kentucky. Arizona recorded the highest temperature, 121 degrees (not a state record at the time).

In July, as the heatwave spread, 22 states reported temperatures over 110 degrees. The highest were in Arizona, Kansas, and North Dakota, with 121 degrees. Oklahoma, North Dakota, and South Dakota reported 120 degrees. The heatwave reached across the continent, from California, with a high of 118 degrees, through Michigan, with 112 degrees, to Pennsylvania, at 111 degrees. Record highs set in 15 of those 22 states during the summer of 1936 were still unbroken in June 2020.

In August, Texas saw 120-degree record-breaking temperatures.

1939-1940

Heat and drought returned. Louisiana experienced 116 consecutive days of 90-degree days between June 6 and Sept. 29, 1939.

By 1941, rainfall levels had returned to near-normal levels. The rains helped to end the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression.

How It Affected the Economy

The massive dust storms caused farmers to lose their livelihoods and their homes. Deflation from the Depression aggravated the plight of Dust Bowl farmers. Prices for the crops they could grow fell below subsistence levels. In 1932, the federal government sent aid to the drought-affected states.

In 1933, farmers slaughtered 6.4 million pigs to reduce supply and boost prices. It successfully increased prices by at least 20%.26 A hungry nation protested the waste of food. In response, the federal government created the Surplus Relief Corporation. That made sure excess farm output went to feed the poor. After that, Congress appropriated the first funds earmarked for drought relief.

Families migrated to California to find work that had disappeared by the time they got there. Many lived in shantytowns called “Hoovervilles”30 named after then-President Herbert Hoover.

By 1936, 21% of all rural families in the Great Plains received federal emergency relief. In some counties, it was as high as 90%.10

In 1937, the Works Progress Administration reported that drought was the main reason for relief in the Dust Bowl region. More than two-thirds were farmers.31 Total assistance was estimated at $1 billion in 1930s dollars.32 The Dust Bowl worsened the effects of the Great Depression.

How It Could Happen Again

The Dust Bowl could happen again. Agribusiness is draining the groundwater from the Ogallala Aquifer at least six times faster than rain is putting it back. The aquifer stretches from South Dakota to Texas and is home to a $20-billion-a-year industry that grows one-fifth of the United States’ wheat, corn, and beef cattle. It supplies about 30% of the nation’s irrigation water.

At the current rate of use, the groundwater will be gone within the century. Parts of the Texas Panhandle already are running dry. Scientists say it would take 6,000 years to refill the aquifer.

Once the water in the Ogallala Aquifer runs out, the Great Plains might become the site of yet another Dust Bowl.

Those who remain will switch to wheat, sorghum, and other sustainable, low-water crops. Some will take advantage of the constant winds that created the Dust Bowl to drive giant wind turbines, a form of renewable energy. A few will allow the grasslands that once dominated to return. That will provide habitat for wildlife, making the area attractive to hunters and ecotourists alike.

ARTICLE SOURCES

- Science News for Students. “The Worst Drought in 1,000 Years.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- National Endowment for the Humanities. “Children of the Dust.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Histories of the National Mall. “DC Invaded by a Dust Storm From Midwest.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- NASA. “NASA Explains ‘Dust Bowl’ Drought.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Oklahoma Historical Society. “Farming.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- NASA. “The Worst North American Drought Year of the Last Millennium: 1934,” Pages 7302-7303. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- EH.net. “The Dust Bowl.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Encyclopedia.com. “Dust Bowl.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- National Weather Service. “85th Anniversary of April 1935 Dust Storm (Black Sunday).” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- National Drought Mitigation Center. “The Dust Bowl.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- EH.net. “The Dust Bowl.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. “The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: The Great Depression 1929-1941,” Pages 53-54. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- The American Presidency Project. “Statement on the Organization of Drought Relief.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- American Red Cross. “Red Cross Timeline.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Google Books. “The Final Frontiers, 1880-1930: Settling the Southern Bottomlands,” Page 84. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Philanthropy Daily. “Herbert Hoover, President-Philanthropist.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. “Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Herbert Hoover,” Page 16. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- NOAA. “Climate at a Glance: National Time Series,” Enter parameters. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- National Weather Service. “The Black Sunday Dust Storm of April 14, 1935.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Encyclopedia.com. “Farm Foreclosures.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- AWS. “74TH Congress. Sess. I. Chs. 84, 85,” Pages 163-164. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- NOAA. “National Climate Report – May 2018 Regional Warmest Summer.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Mortality Statistics 1936,” Page 138. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- NOAA. “Data Tools: Daily Weather Records: View Selected Records,” Enter parameters. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- NOAA. “Climate Data Online Search: Daily Summaries,” Enter parameters. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. “The Porcine Slaughter of the Innocents.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- The American Presidency Project. “Statement on the Federal Surplus Relief Corporation.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- National Archives. “Records of the Surplus Marketing Administration.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Google Books. “Decisions of the Comptroller General of the United States,” Pages 103-104. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Library of Congress. “America From the Great Depression to World War II: Black and White Photographs From the FSA and OWI, ca. 1935-1945.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Research Bulletin Relief and Rehabilitation in the Drought Area,” Page 3. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis. “Climatic Change and Human Activities,” Page 111. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- U.S. Geological Survey. “Recharge Rates and Chemistry Beneath Playas of the High Plains Aquifer—A Literature Review and Synthesis,” Pages 5-7. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- PNAS. “Tapping Unsustainable Groundwater Stores for Agricultural Production in the High Plains Aquifer of Kansas, Projections to 2110.” Accessed June 9, 2020.

- Scientific American. “The Ogallala Aquifer: Saving a Vital U.S. Water Source.” Accessed June 9, 2020.