“By Saint Denis, girl,” quoth he, “you have a proper spirit, but it takes more than a pair of breeches to make a man.”

“If that other woman of whom you spoke could march and fight, so can I!” I cried.

“Nay.” He shook his head. “Black Margot of Avignon was one in a million.”

— Robert E. Howard, “Sword Woman”

Etienne Villiers, later to be Agnes de Chastillon’s comrade, was born in 1493 by my reckoning. At that time Guiscard de Clisson, who would tell Agnes of the remarkable Black Margot, was twelve, and Margot herself was in Italy – first in Milan and then in the Florence of Piero de Medici and Savonarola. Pope Innocent VIII had just died, and Rodrigo Borgia had succeeded him as Alexander VI. He would be remembered, with cause, as the vilest, most corrupt Pope in history.

In 1494, King Charles of France entered Italy by way of Piedmont on a military expedition. His forces were formidable – 25,000 men, among them 8,000 Swiss mercenaries, and he brought artillery with him. His dubious claim to Naples was the pretext; the late King Ferdinand of Naples had refused to pay feudal dues to the Papacy, and been excommunicated. Innocent III had then offered the crown of Naples to King Charles of France, who had a remote hereditary claim. The quarrel between Ferdinand and the Pope was later mended, and Innocent revoked the ban of excommunication before he died. Ferdinand also died shortly afterwards, at the beginning of 1494, and was succeeded by his son Alfonso II. The matter of Charles’s claim might have rested there, but Milanese politics arose to complicate matters. Alfonso challenged Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, since Alfonso also had a claim to rule that city, so Ludovico decided to remove the threat by urging Charles of France to conquer Naples. Certain fellow schemers also desired the French invasion; Charles’s favorite courtier, Etienne de Vesc, and the Cardinal Guiliano della Rovere, who didn’t like the Borgia Pope and hoped the French campaign would result in his overthrow, or at least weaken him. Charles marched on Pisa, and arrived before Florence in November.

Pierre de Bayard, twenty-one years old, went with the French forces. Margot of Avignon, nineteen, heard of their advance and enthusiastically joined them, meeting them outside Florence. Like Dark Agnes after her, Margot had to fight several men in order to be taken seriously, and for that matter avoid rape. Bayard heard about the matter, even witnessed one such event, and took Margot’s part. He was chivalrous, but conventionally so, and thus always felt quite baffled by Margot. But he treated her as a comrade-in-arms.

We can suppose that a far less gallant person than Bayard was also with the French army – Dark Agnes de la Fere’s father, the illegitimate child of a peasant woman and the Duc de Chastillon, as Agnes tells Etienne in “Sword Woman”, who “ever used the name, and his daughters after him.” Those daughters would not be born until six and ten years later, after de Chastillon had become “marked with scars … in the service of greedy kings and avaricious dukes” and “looted and murdered and raped as a Free Companion”. Perhaps de Chastillon was even one of the men who attempted to rape Black Margot, and one or more of his scars came from her, as she forcibly taught him to have better manners … with her, at least. No doubt he hated her afterwards and would have done her an ill turn at any chance that offered.

He never mentioned her in the village where he ended his days as a married man. It would have hurt his pride. Agnes was evidently hearing about her for the first time when Guiscard de Clisson spoke of Margot so admiringly.

On their way to Naples, the French easily crushed the small armies the Pope and the Neapolitans were able to send against them. They also responded with bloody massacre in any town that resisted them. Their savagery appalled the Italians, who were used to small wars conducted by contract. Bodies of businesslike condottiera carried them out, seeking to take prisoners for ransom and minimize bloodshed, since an enemy this year might well be their employer next time. The French invaders made war in a very different fashion.

With Charles’s army outside their walls, the terrified Florentines exiled their Duke, Piero de Medici (known thereafter as “the Unfortunate”) and surrendered on terms. Under Bernardo Rucellai and other prominent Florentines, they formed a republic. They suffered plunder but not wholesale slaughter, though the mercenaries and other soldiers in their city were brutal whenever it suited them. 1494 went out and 1495 came in. The French army reached Naples, which yielded in February without one pitched battle or even a siege. The French remained there for three months, and systematically plundered the city. The usual assaults and outrages occurred. During those three months, Margot filled her pockets as never before, and enjoyed luck at dice besides.

While Naples was being rifled, the other Italian states realized that the French would not be content with that city. They were all staring foreign conquest in the face. The Pope, the Holy Roman Emperor (who also ruled Spain) and Venice, formed the so-called Holy League in March. Milan also joined it. Charles saw that this opposition was too powerful for his army to trounce, and so he retreated by way of Rome. Even though pursued by their opponents, the French halted long enough to plunder that city too. Pope Alexander had left in a hurry, abandoning Rome to the invaders.

The Holy League’s army, commanded by the condottiere Gonzaga, caught the French near Parma in Lombardy. The battle of Fornovo followed, on the 6th of July. The actual fight lasted just fifteen minutes. The French were short on provisions, and an army, as always, marched on its stomach. Rain had drenched their powder, too, and so their artillery was disabled. The battle was hardly a conclusive victory for either side, and the French lost only about a thousand men, but they were deprived of their baggage train with the rich plunder of Florence, Naples and Rome. Naples was regained after Charles had left it; he went home with nothing. About the only person on the French side who came out of it with credit was Pierre de Bayard, who captured an enemy standard single-handed and was knighted after the battle.

Margot was disgusted by what she considered the weak-kneed ineptitude of the whole campaign. She had displayed fierce energy and powers of leadership, and a small company of mercenaries left the French forces with her, hailing her as their captain. They took service in the Duchy of Savoy, then ruled by a child, another Charles, Duke Charles II. Blanche of Montferrat, his mother, then aged twenty-three, was regent and the actual ruler. (She had married the former Duke of Savoy when she was thirteen, and been widowed at eighteen.) The ruling house of Savoy was effectively under the thumb of France and came to reside in Turin during these years. The Duchess Blanche hired Margot and her company as a kind of roving trouble-shooters – and there was trouble in plenty to shoot. Aside from French and Italian agents, brigands, and traitors, there was also one case of cruel depredations by a werewolf.

Margot of Avignon had a particular dread and hatred of loup-garous. Her parents had been killed by one when she was a child. She constantly carried a silver dagger, just in case. This particular beast was a sorcerer who had become a werewolf by choice, using an enchanted wolfskin belt. He had been hired to assassinate the child duke. Black Margot prevented the murder and killed the werewolf, for which the regent made her commander of her elite guard. She wishfully thought this monster the same one that had murdered her parents, but it wasn’t; that had been de Montour, and he was then in West Africa, as narrated in REH’s story “Wolfshead.” Black Margot never encountered or even heard of him.

Sadly, her rescue of the child duke did not prolong his life by much. He died by mischance in April of 1496, in a fall at Moncalieri. With his death the Duchess Blanche ceased to be the regent and ruler of Savoy. Black Margot had many enemies, some of them simply because they thought she was too far above her proper station as a woman. They took the opportunity to outlaw her and drive her from Savoy. Margot returned to Avignon, where the papal legate at that time was Archbishop Francesco Tarpugi. (Previously it had been Giuliano della Rovere, later to become Pope Julius II.) A church council took place there in 1497. After the council Tarpugi was made a cardinal, but it had no other significant outcome; no major decisions were reached. It was decreed that sponsors of the newly confirmed were not obliged to give presents, and that two candles were to be kept burning constantly before saintly relics.

Between 1496 and 1499, Black Margot made her way as a bravo in Avignon, Arles and Aigues-Mortes in the Camargue. That wild beautiful country had always fascinated her, with its marshes, lagoons and wild white horses. During those three years she encountered another lycanthrope, but this was no shape-shifter, merely a poor madman who believed he was a wolf and behaved like one. She intervened to save him from being burned by a mob, but later had to kill him herself to rescue a young couple from his deranged savagery.

In 1498 King Charles VIII of France died, after accidentally hitting his head on a doorway in Amboise. He left no heir. His cousin Louis of Orleans then became king as Louis XII. Earlier, he had been one of the great nobles who opposed the French crown in the “Mad War” (see “The Other Sword Woman: Part One”). His uncle, Louis XI, the “Universal Spider” had married him by compulsion to his handicapped and sterile cousin Joan, in a deliberate attempt to make his line extinct. Louis of Orleans had been pardoned after the “Mad War” and was one of the French commanders in the Italian War of 1494, in which Black Margot and Bayard had also taken part. On becoming king, he at once prevailed on the Pope to annul his marriage to Joan. He then married Anne of Brittany, his cousin’s widow, instead.

Now, determined to press his claims to Naples and Milan, he invaded Lombardy in 1499. Black Margot followed the French banners. So did Bayard, and so did Guiscard de Clisson, who at that time was eighteen. (This blogger believes he was a descendant of Olivier de Clisson, Constable of France between 1380 and 1392.) Pope Alexander supported the campaign, in exchange for military support from Louis for Cesare Borgia’s campaigns in the Romagna. Margot was always in thick of the fighting, first around Naples, then when the alliance between the French and Aragonese failed and their forces clashed over the spoils. There was also constant bickering and bawling between the Italian and French knights. Finally, at the end of April 1503, the battle of Cerignola was fought between the French and Spanish, resulting in a French defeat and the death of the Duke of Nemours.

At the end of that year, shortly after Christmas, the Battle of Garigliano was fought. The result was another French defeat at Spanish hands, and the fight is mainly remembered because of Pierre de Bayard’s heroic defense of the bridge against overwhelming odds, giving the French their chance to retreat without further losses. Black Margot stood with him at the bridge and was killed there by a pistol – or musket – ball. The twenty-two year old Guiscard de Clisson saw her fall, and never forgot her.

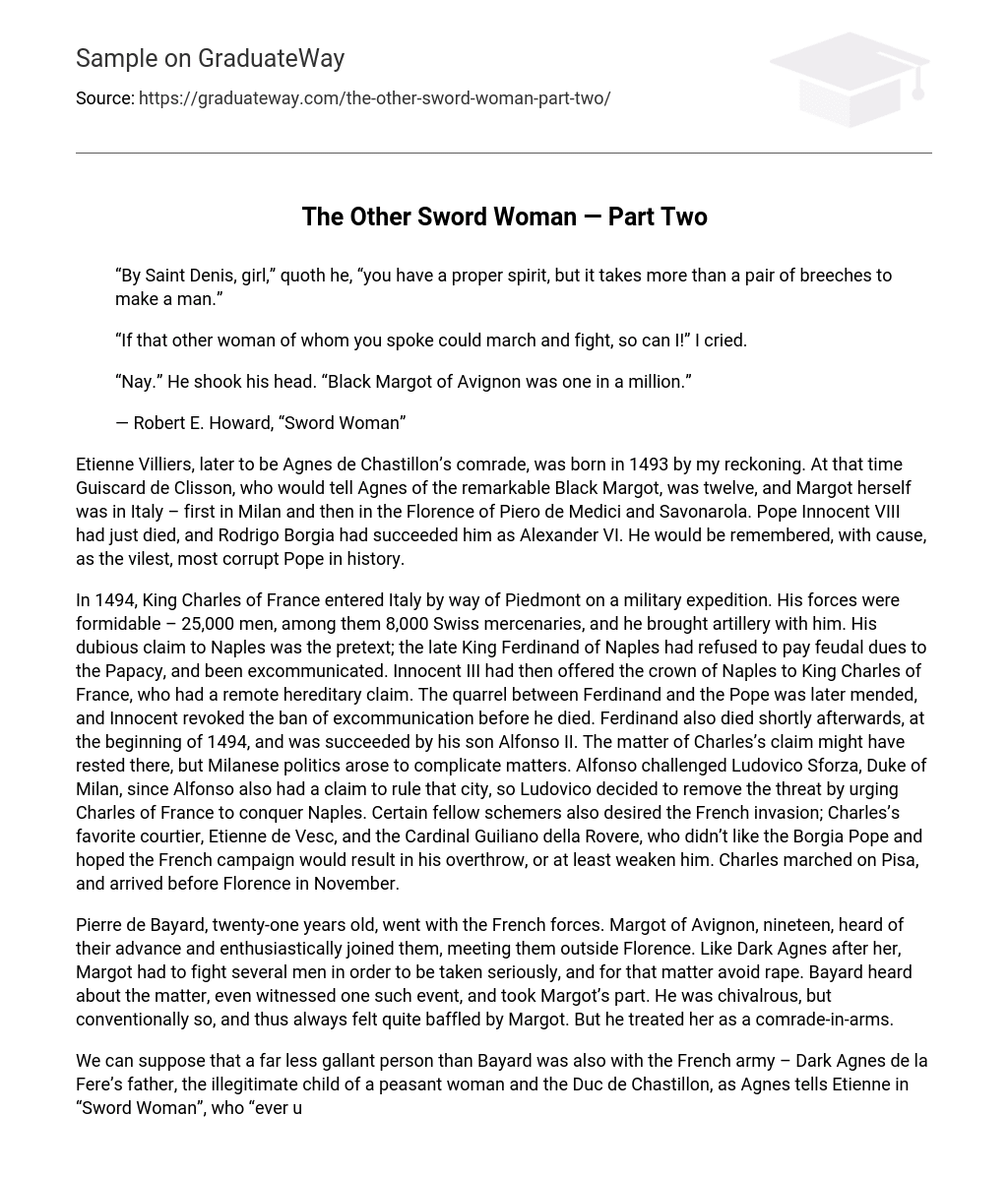

Art credit: Dark Agnes de Chastillon by Mark Schultz

Read Part One