The Standing Parvati originated in the Chola Period circa 880-1025 AD, a time when bronze statues grew increasingly in number to meet the demands of a changing religious and social lifestyle. Alterations within the Hindu religion called for moveable statues that could be carried outside of temples to participate in rituals. The old stone sculptures of Hindu deities were stationary, so artisans turned to the casting of metal as a new approach to creating religious art patronized by the Chola rulers.

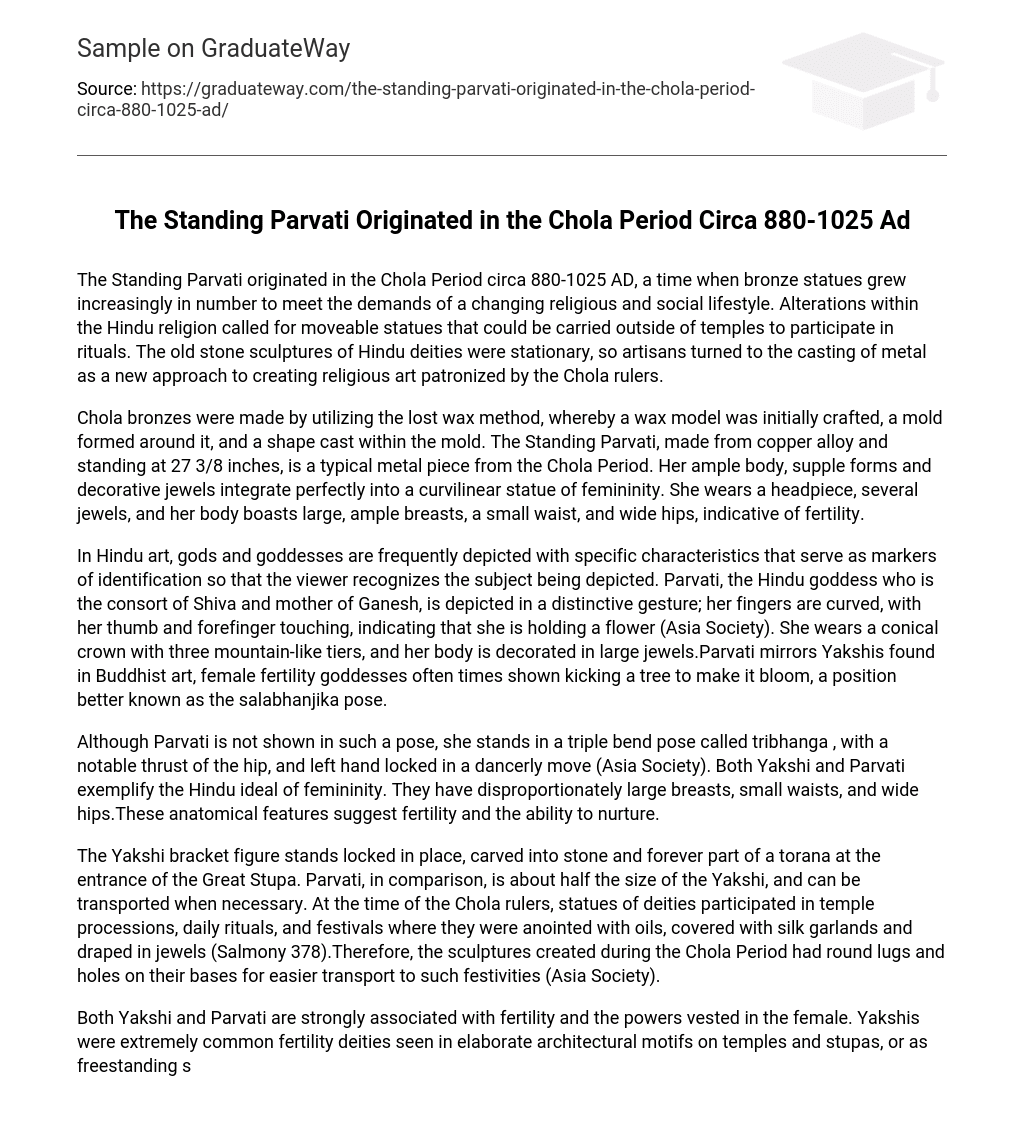

Chola bronzes were made by utilizing the lost wax method, whereby a wax model was initially crafted, a mold formed around it, and a shape cast within the mold. The Standing Parvati, made from copper alloy and standing at 27 3/8 inches, is a typical metal piece from the Chola Period. Her ample body, supple forms and decorative jewels integrate perfectly into a curvilinear statue of femininity. She wears a headpiece, several jewels, and her body boasts large, ample breasts, a small waist, and wide hips, indicative of fertility.

In Hindu art, gods and goddesses are frequently depicted with specific characteristics that serve as markers of identification so that the viewer recognizes the subject being depicted. Parvati, the Hindu goddess who is the consort of Shiva and mother of Ganesh, is depicted in a distinctive gesture; her fingers are curved, with her thumb and forefinger touching, indicating that she is holding a flower (Asia Society). She wears a conical crown with three mountain-like tiers, and her body is decorated in large jewels.Parvati mirrors Yakshis found in Buddhist art, female fertility goddesses often times shown kicking a tree to make it bloom, a position better known as the salabhanjika pose.

Although Parvati is not shown in such a pose, she stands in a triple bend pose called tribhanga , with a notable thrust of the hip, and left hand locked in a dancerly move (Asia Society). Both Yakshi and Parvati exemplify the Hindu ideal of femininity. They have disproportionately large breasts, small waists, and wide hips.These anatomical features suggest fertility and the ability to nurture.

The Yakshi bracket figure stands locked in place, carved into stone and forever part of a torana at the entrance of the Great Stupa. Parvati, in comparison, is about half the size of the Yakshi, and can be transported when necessary. At the time of the Chola rulers, statues of deities participated in temple processions, daily rituals, and festivals where they were anointed with oils, covered with silk garlands and draped in jewels (Salmony 378).Therefore, the sculptures created during the Chola Period had round lugs and holes on their bases for easier transport to such festivities (Asia Society).

Both Yakshi and Parvati are strongly associated with fertility and the powers vested in the female. Yakshis were extremely common fertility deities seen in elaborate architectural motifs on temples and stupas, or as freestanding statues.Hindu, Buddhist and Jain religions worship Yakshis as Mother Goddesses, perhaps similar to the Western concept of Mother Nature. Although Parvati is not exclusively a fertility goddess, she is the consort of Shiva and an integral aspect of his power, embodying the essence of the female and symbolizing the fruitfulness of man and the universe (Far Eastern Scripture 418).

Parvati is an intrinsic manifestation of the Great Mother and of the Godhead itself (Far Eastern Scripture 418).