Violence on TelevisionWe hear a great deal about violence on television thesedays. Nearly everywhere you turn there is something beingwritten about it, or a program dealing with the issue of it, or anews story about a child somewhere who was influenced by it to dosomething harmful. The subject permeates our collectiveconsciousness. Maybe this is due to the ever-increasing numberof gangs in our urban centers. Maybe it’s due to theever-increasing crime rate that we hear about almost nightly onthe news. Whatever the reasons behind its being such a concern,the fact remains that violence on television is a very realproblem that is quite definitely a contributing factor toincreasing violence among children and, yes, even among adults.

Cartoon violence has been around as long as cartoons have -and that’s a long time. The first animated Disney cartoonsfeatured a rabbit named Oswald back in 1928 and the cartoonindustry grew from there. So for seventy years now we’ve beentreated to the antics of various characters, either through theopening Looney Tunes at the movies or the five hours of Saturdaymorning cartoons that were a ritual with us all growing up.

There was Tweety Bird always getting the best of Sylvester theCat, Bugs Bunny always outsmarting Elmer Fudd and Daffy Duck,Foghorn Leghorn constantly getting bruised by the awkward anticsof his little chicks, Yosemite Sam getting his head blown off atleast once a week and of course, the memorable Wyle E. Coyotewho never, in all his forty-odd years of pursuing the Roadrunnerever bought anything from the Acme Co. that ever worked right(Siano, 20).

They were truly funny and, in some respects, cathartic forus and it is this writer’s opinion that cartoon violence is quiteprobably the least of our worries as far as what is corruptingthe minds of our children today. We grew up on it and there isnot one single documented case of a violent criminal who everclaimed that he ended up the way he did because he ingested asteady diet of Roadrunner episodes. Let’s get serious. Most ofthese violent criminal types weren’t home with the familywatching Saturday morning cartoons when they grew up. They wereout tying cats’ tails together and throwing them over somebody’sclothesline so they could watch them kill each other. Or theywere torturing the neighbor’s new puppy while Mom was at work,Dad was non-existent, and all 3 or 4 or 5 kids were left to raisethemselves. Or they were busy learning violence first-hand fromtheir alcoholic father whose chief mission in life seemed to beusing them and their siblings and their mother for a punchingbag.

The difference, I would submit, is that even the smallestchildren understand that these are cartoon characters, that theyare not real, and that the violence depicted in cartoons is sounrealistic that even small children realize that it’s purelymake-believe.

Is television really toxic to children? (Chidley, 36). AsDavid Link says, “The problem isn’t that people pay too muchattention to the violence that appears on television; the problemis they pay too little,” (22). Mr. Link proposes thatfictional violence is not at the root of the problem, but thereal violence that is depicted daily on television that should beour biggest source of concern. In this, he has a very validpoint. Does a rabid, demon-possessed little doll named Chuckiereally influence anyone as he stabs people ten times his sizewith a little knife barely long enough to break through all ofthe layers of a person’s skin? Is that ghoul riding in thebackseat of the car, with his face falling off all over the placeas he strangles the teenage driver really believable?In fiction, there is a thing called “willing suspension ofdisbelief.” This must be achieved in order for the personreading, or viewing, a fictional story to be able to participatein the story. It’s what holds the reader’s attention. It’s whatcauses us to cry when the heroine dies; or when we find out theboy’s dog really wasn’t dead after all and he comes running homeat the end; or when the ghost of the woman’s husband finallymakes contact with her and gives her one last kiss followed by,”I will always love you.” Willing suspension of disbelief iswhat keeps all those Harlequin Romances selling; it’s what madeDanielle Steel rich and Ernest Hemmingway famous. And it’s whatmade Arnold Schwarzenegger a star.

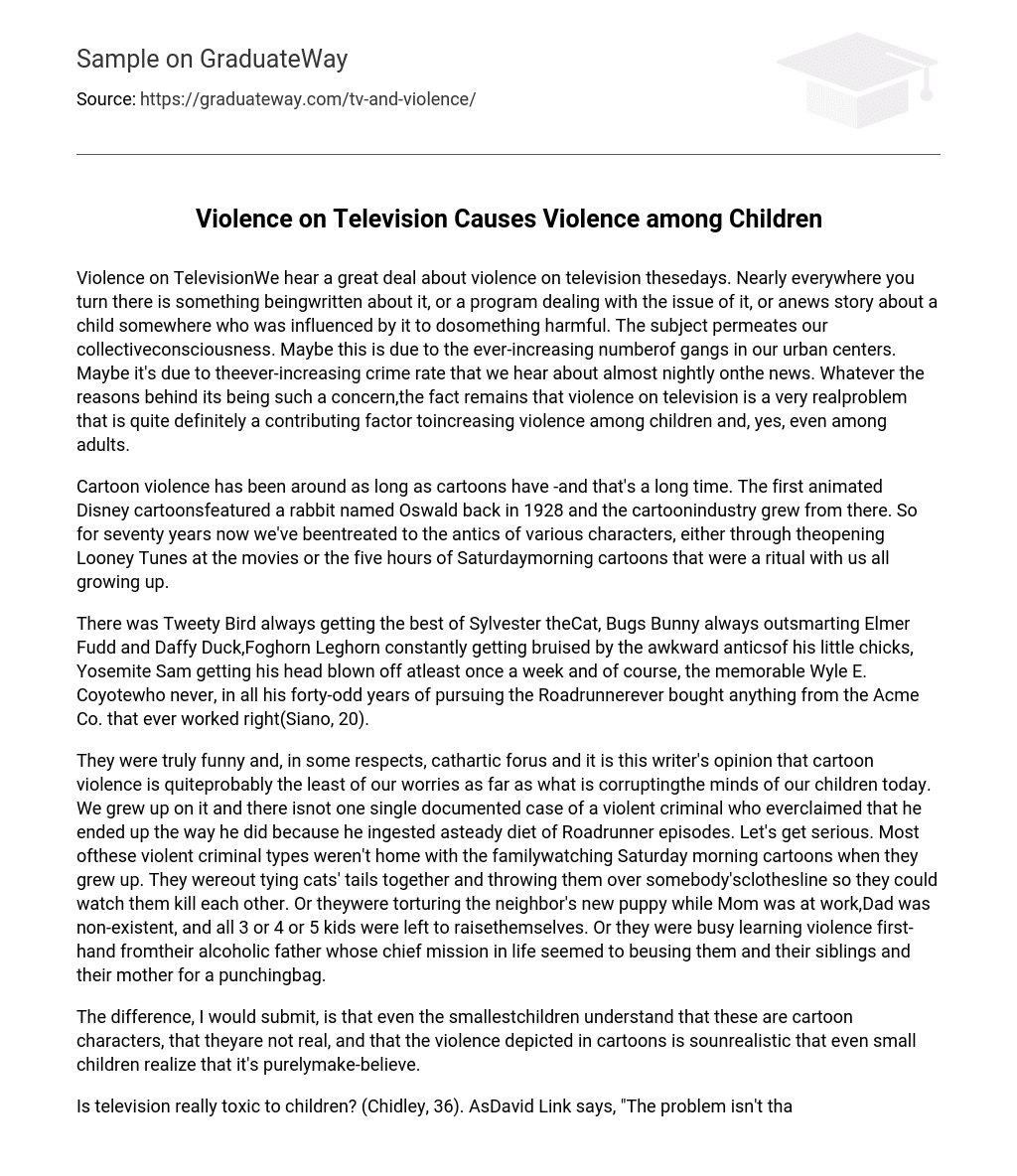

But is it what makes murderers out of 12-year old boys? Orarsonists out of 10-year olds? There are certainly those whowould have us believe that it does. According to a 1996 surveyof television violence the following statistics were cited.

Programming Violence on Television, by Network TypePublic Broadcasting Systems (PBS) 18%Broadcast networks 44%Independent broadcast 55%Basic cable 59%Subscription television, premium cable 85%Source: Mediascope, Inc., February, 1996 (Women, 11).

The argument, as women’s groups have set forth goessomething like this: it is children’s programming that is of themost concern. Why? Because of two reasons. The first is thatvery often violence (in 67% of programs surveyed) is portrayed ina humorous context. The second is that in 5% of programs,violence is not portrayed with any associated consequences to it.

Those opposed to television violence claim that it isresponsible for the rise in violence in schools and classrooms(Feigenbaum, 2). In particular, educators claim that if violenceon television were curbed, children would be less violent inschool, that children are mimicking what they see acted out onthe television screen. In 1995, the V chip bill was introducedinto Congress. It’s purpose was to impose a rating system upontelevision programs so that parents could monitor the types ofprograms their children were watching a bit more closely. That’snot a bad idea, since there are times when one turns on aspecific program thinking it will be all right for viewing byone’s 3rd grader, only to find, part way through it, that there’sgoing to be a bedroom scene that doesn’t leave a lot to anyone’simagination. However, no matter what bills and legislation areintroduced and actually made into law, that does not preclude thefact that parents must have the will and inclination to instillin their children the values necessary to respect themselves andothers and if parents are doing their jobs with regard to this,nothing that comes across in television will affect that.

Yet even with this, one has to ask some very importantquestions: If people are watching television with their children,how can those children not know or understand that this violenceis not real? How can they not understand the difference betweenreality and make-believe? And if they don’t, is it because theirparents are letting the television raise the children for them?In actuality, the biggest problem that occurs as a result ofrepeated exposure to violence on television is desensitization toscenes of violence (Hough, 411). This is very real and occursfrequently. For example, consider the woman who did not feelthat her son was watching enough television (or televisionviolence) to affect him, and yet when driving past an automobileaccident one day was appalled when her young son excitedly askedher to turn around and go back so he could see the person lyingon the side of the road again.

As David Link further states, it’s not the fictionalviolence on television that we need to worry about, but thefactual violence that is causing problems. When the kids sitdown with Mom and Dad while they watch the news at night and getto see real-life scenes of death and dismemberment, violence forthem takes on an entirely different meaning.When Dad andJohnny spend Sunday afternoon watching the football game and fourplayers from the two teams end up duking it out on the playingfield because of a bad call by one of the referees, there’s amessage that gets sent to the kids that should be of much moreconcern to us than the fact that Daffy Duck just got his beakblown off for the four thousandth time.

When Dennis Rodman falls out of bounds during a Bulls game,kicks a cameraman in the crotch for no reason, gets up laughingabout it, and we all get to watch it on the news, something isterribly wrong. What does this teach our children? This is NOTmake-believe. This is the real world and kids know it.

When the Undertaker gets insulted by another wrestler and hepicks the guy up and throws him out of the ring – and they aren’teven having a match yet – there’s a message that comes across tothe kids that it’s okay to use violence when you get mad atsomeone.Wrestling, particularly WWF wrestling, is probably oneof the worst things for kids to watch due to the fact that,although almost all of it is stuntwork, kids don’t realize that.

And when Mom or Dad tries to explain that to the kids, they don’tbelieve it. There is no way for the kids to understand that it’sall show. And heaven help it if someone actually starts to bleedwhile in the ring because that only adds to the realism that muchmore and completely convinces the kids that this is, indeed,real.

Legislation is not the answer to this however. The answerto this lies in those who are icons to children takingresponsibility for their behavior in front of the camera so thatthey are not giving the wrong message to these children. Rodmanis a case in point. Young boys, in particular, look up to probasketball players and when they see someone intentionally hurtsomeone else for no reason other than they are angry atthemselves, or angry at their circumstances, the message that itis all right to take your anger out on whomever has themisfortune to be in your way at the time comes through loud andclear.

David Link is absolutely right. Fictional violence is notthe problem and, if more parents paid attention to the true,real-life, up-to-the-minute violence their kids were experiencingevery day, they would realize just how harmless all thoseRoadrunner cartoons really are – and just how serious a problemwe are creating through media sensationalism.

Words/ Pages : 1,648 / 24