EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Since Israel’s 1967 occupation of the West Bank, including Jerusa- lem and Gaza, it is estimated that Israeli civil and military authorities have destroyed 24,000 Palestinian homes in the occupied Palestinian territory (OPT). The rate of house demolitions has risen significantly since the second Intifada began in September 2000 and, as this study shows, house demolitions have become a major cause of forced displacement in the OPT. When a home is demolished, a family loses both the house as a financial asset and often the property inside it.

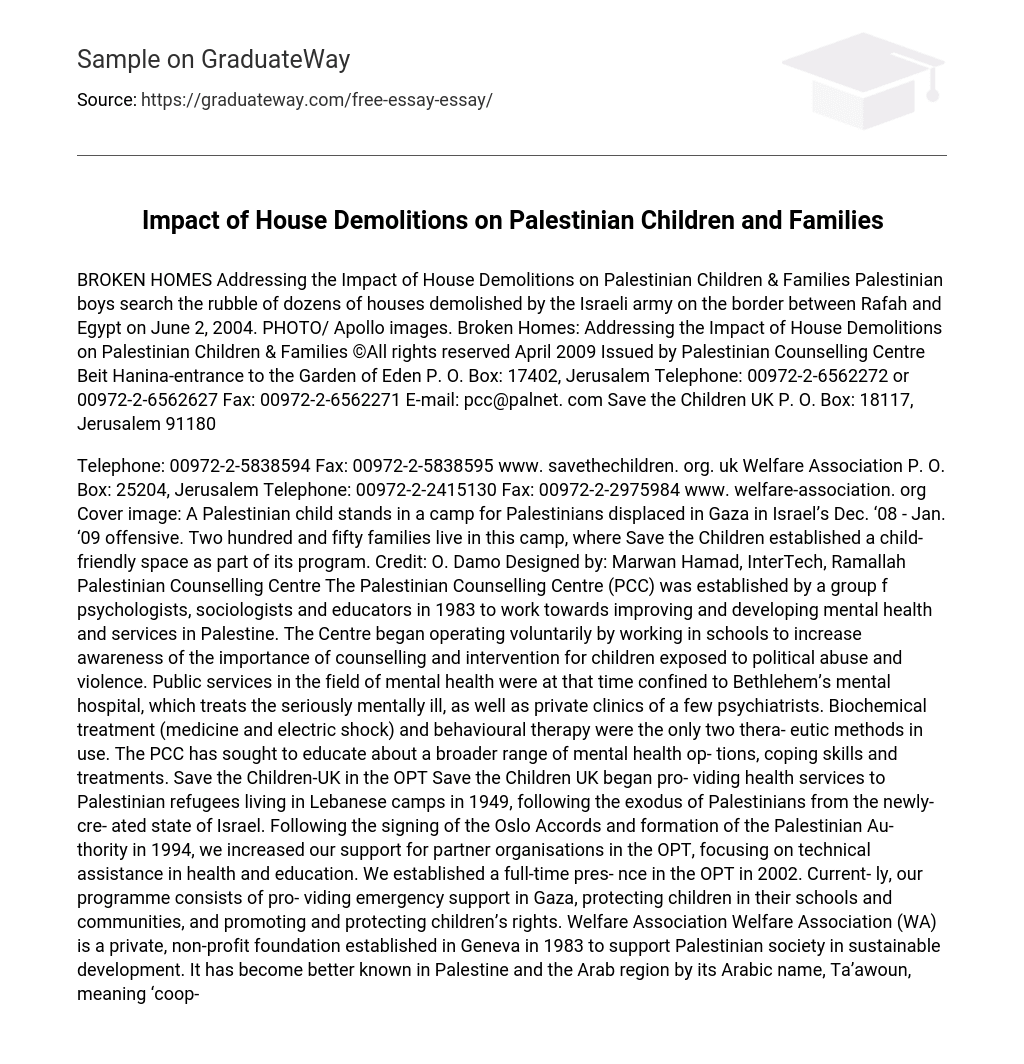

For the families surveyed in this study these losses respectively totalled an average of approximately $105,090 and $51,261 per family. 1 But the impact goes beyond loss of physical property and economic opportunity. This report is unique in the connection it makes be- tween the impact of house demoli- ions on children and their families, and the responsibility of duty bear- ers to protect and assist.

Using structured mental health questionnaires, semi-structured questionnaires of the family’s demolition experience and socio- economic conditions, and open interviews with families, this study depicts a portrait of Palestinian families who have experienced house demolitions. This depiction enables the humanitarian commu- nity to better advocate for an end to demolitions and, in the interim, put in place a comprehensive and coordinated response for families who are facing displacement due to demolition or other factors. They told us that we could return at five o’clock, but where were we supposed to go after they demolished our home?

It’s gone. ” The main findings of the study were: House demolitions cause dis- placement. Fifty-seven percent of 56 families surveyed never returned to their original resi- dences. Those who did return, on average, spent over a year displaced before returning. House demolitions are fol- lowed by long periods of instability for the family, with over half of the families who responded taking at least two years to find a permanent residence. At the time of interviewing, the average monthly income of amilies surveyed was NIS1,561 (USD 355) – well below both the absolute (deep) and rela- tive poverty lines.

Compared to children of similar demographics living in the same geographical locations, children who have had their home demolished fare significantly worse on a range of mental health indicators, including: withdrawal, somatic complaints, depression/anxiety, social diffi- culties, higher rates of delusion- al, obsessive, compulsive and psychotic thoughts, attention difficulties, delinquency, violent behaviour – even six months after the demolition.

Families also report deteriora- tion in children’s educational chievement and ability to study. A fundamental factor affecting the child’s mental health follow- ing demolition is the psycho- logical state of the parents, yet one-third of the parents were in danger of developing men- tal health disorders and some reported that the demolition precipitated a decline in their physical health also. The social support that par- ents receive and their ability to employ coping strategies for themselves and their children (usually determined by proxim- ity to the original home and the family’s cultivated network of resources) may mitigate some of the detrimental effects.

Maintaining the mother’s mental health is particularly crucial for children under 12. Based on its findings, the study recommends that all stakeholders-Israel, the Palestinian Authority, the international community and donor governments- act immediately to respond to house demolitions within the OPT by fulfilling their obligations to protect children and their families according to international humanitarian and international human rights law, in particular the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement.

In particular, the report’s authors call on Israel, the ccupying power in the OPT, to halt the policy of house demolitions, which violates its responsibil- ity to protect the civilian population in accordance with the laws of armed conflict and human rights law. Alongside advocacy on prevention, the interna- tional community (including donor governments) should support a United Nations-led inter-agency response to alleviate the wide range of health, so- cial and economic problems resulting from house demolitions and the broader problem of forced displacement in the OPT.

INTRODUCTION HOUSE DEMOLITIONS AND INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT IN THE OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORY

Far from being confined to a discrete war in 1948, the conflict which triggered Pales- tinian flight has persisted over six decades… In the occupied Palestinian territory, refugees are repeatedly displaced in the wake of armed incursions, home demolitions and air strikes-and even checkpoints and the separation barrier. ” —United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) Commissioner General, Jan. 2008 The demolition of a home not only destroys a physical structure, but has numerous other consequences: it tears down the family structure, increases poverty and vulnerability, and ultimately displaces a family rom the environment that gives it cohesion and support. This has long term physical and mental health consequences.

While forced displacement is an acknowledged part of Palestinian history, it is often discussed as a limited historical phenomenon that occurred during the Arab-Israeli wars that produced hundreds of thousands of refugees and inter- nally displaced persons (IDPs). But Palestinians, both refugee and non-refugee, are still being dis- placed today. One of the primary vehicles for their displacement is the Israeli policy of house demoli- tions. In recent years, ongoing internal displacement in the occupied

Palestinian territory (OPT) has received increasing attention from international human rights, humanitarian and development agencies. Nevertheless, monitor- ing and documentation of internal displacement in the OPT has been largely ad hoc, and the numbers of internally displaced and the impact of displacement on their lives have not been systematically recorded. In an effort to contribute to this expanding discussion, our study presents a portrait of families whose houses have been demol- ished, emphasizing the mid- and long-term impact of house demoli- tion on children and families.

We have asked these families ques- ions related to their economic status, mental and social health, and the fulfilment of basic needs: food, education, and housing. “There are numerous interacting social, psychological and biological fac- tors that influence whether people develop psychological problems or exhibit resilience in the face of adversity,” 3 and this study seeks to illustrate these various influences. In addition, the study makes a preliminary assessment of these families’ ability to return to their places and communities of origin or resettle to a new community, and the impediments that may subsequently arise.

We are concerned that families ho experience house demoli- tion fall into a protection abyss, without a coordinated safety net to support them and their additional needs. This paper concludes therefore by outlining the basic principles 10 Children are deeply impact- ed by house demolitions.

In Gaza, 35,224 children were impacted when 7,342 houses were entirely or partially destroyed by Israeli forces between 2000 and 2007. 28% of children surveyed in Gaza had witnessed the demolition of a friend’s home and nearly 19% had witnessed the demolition of their own home. for an appropriate response to house demolitions, making recom- endations for the Israeli govern- ment, the Palestinian Authority, the international community and civil society groups, while keeping in mind the broader framework of forced displacement.

HOUSE DEMOLITIONS: A BACKGROUNDER

Since Israel’s 1967 occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, it is estimated that Israeli civilian and military authorities have destroyed 24,130 Palestinian homes in the OPT. The rate of house demolitions and evictions has risen significantly since the beginning of the second Intifada in September 2000. Ac- c ording to the Israeli Commit- tee against House Demolitions (ICAHD), between 1994 and 2000 hen Palestinians and Israelis were engaged in negotiations, 740 Pales- tinian homes were demolished in Israeli military operations.

By comparison, between October 2000 and 2004, 5,000 homes were demolished during military opera- tions. 6 The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) systematically began tracking homes demolished in the OPT in 2006. From that year to July 2008, 989 structures were demolished (639 in the West Bank and 350 in the Gaza Strip), of which 52% were residential. While this appears to mark a decline in the number of homes demolished, ICAHD notes that Israeli authori- ies have demolished increasingly larger structures, which house more people.

The demolition of homes causes the forced displacement of their residents. In the West Bank alone, the destruction of some 3,302 homes between 2000 and 2004 meant the displacement of ap- proximately 16,510 people. The Israeli incursion into Jenin Camp in 2002 displaced approximately 4,000 people. Nearly all of the 232 people displaced in Nablus over the past two and a half years lost their homes in military operations. Tens of thousands of additional homes have been damaged to the point of being uninhabitable during military incursions.

In Gaza, from 2000 to 2007, the partial or total destruction of 7,342 houses, largely as a result of Israeli military activity, impacted 69,350 residents, among them 34,224 children. During 2008, 1,151 Palestinians- including a confirmed 419 children and an additional estimated 194 children 10 – were displaced or af- fected 11 by the demolition of 156 residential structures in the OPT.

Of these, 87 houses were demol- ished and 404 Palestinians (includ- ing 227 children) were displaced in East Jerusalem alone. 13 In addition, over 4,000 homes were demol- ished between 27 December 2008 and 18 January 2009 during Israel’s 11 ilitary operation in Gaza 14 and at the peak of hostilities, 200,000 people were estimated to be displaced-among them 112,000 children. In a 2008 Gaza study, 28 percent of children surveyed had witnessed the demolition of a friend’s home and nearly 19 percent had wit- nessed the demolition of their own home.

WHY ARE HOUSES DEMOLISHED?

Various explanations are given by Israeli authorities for the de- molition of Palestinian homes. The Israeli human rights group B’Tselem documented the official reasons given for the demolition of over 4,100 Palestinian houses in the OPT between 2000 and 2004. Sixty percent were demolished n ‘clearing operations’ (i. e. mass demolitions); 25 percent were destroyed for the lack of build- ing permits; and 15 percent were destroyed as punishment against accused militants.

In this latter case, 32 percent of the individuals were in Israeli detention, 21 per- cent were ‘wanted’, and 47 percent were already dead. 18 When the homes of suspected militants are demolished, they are usually de- molished without prior warning. In some cases, residents were not able or were not given the oppor- tunity to evacuate and died in the building’s collapse.

SECURITY RATIONALE

When demolishing houses of Pal- stinians suspected of committing security offences, Israeli authorities refer to article 119 (1) of the 1945 Defence (Emergency) Regulations approved by the British govern- ment at the time of the British Mandate in Palestine: A Military Commander may by order direct the forfeiture by the Govern- ment of Palestine of any house, structure, or land from which he has reason to suspect that any firearm has been illegally discharged, or any bomb, grenade or explosive or incendiary article illegally thrown, or of any house, structure or land situated in any area, town, village, quarter or street the inhabitants or some of the nhabitants of which he is satisfied have committed, or attempted to commit, or abetted the commission of, or been accessories after the fact to the commission of, any offence against these Regulations involving vi- olence or intimidation or any Military Court offence; and when any house, structure or land is forfeited as afore- said, the Military Commander may destroy the house or the structure or anything growing on the land.

The Israeli Supreme Court regards the Defence (Emergency) Regula- tions as a section of Israeli local law, despite the fact that they were rescinded at the end of the British Mandate. Israeli authorities began applying those regulations to the OPT in 1967.

ADMINISTRATIVE RATIONALE

Due to restrictive zoning and urban planning, bureaucratic and financial obstacles, Palestinians seek to resolve urgent housing needs by building without an official permit, despite the risk of subsequent 60% of 4,100 Palestinian houses demolished between the years 2000 and 2004 were demolished in military ‘clearing’ operations. 25% were destroyed for lack of building permits. 15% were destroyed to punish accused militants. Three-hundred and twenty-five homes, over half (184) of them in Jerusalem, were demol- shed in the West Bank due to the lack of building permits between the years 2004 and mid-2007, ac- cording to B’Tselem.

Throughout the West Bank, but in Jerusalem in particular, observ- ers note clear discrimination in the application of building regu- lations and punishment meted out. Between 1996 and 2000, for example, the number of recorded building violations was four and a half times higher in Israeli neigh- bourhoods of Jerusalem (17,382 violations) than in Palestinian neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem (3,846 violations). But the number of demolition orders over this pe- riod issued in West Jerusalem was our times less (86 orders) than the number in East Jerusalem.

“In other words, while over 80 percent of building violations were recorded in West Jerusalem, 80 percent of actual demolition orders were issued for buildings in Palestin- ian East Jerusalem,” according to the World Bank. 26 Between 1999 and 2003, 157 Palestinian-owned build- ings were demolished in Jerusalem by Israeli authorities, compared to only 30 Israeli-owned buildings. Many families continue to live with the threat of displacement through house demolition. In 2005, there were more than 10,000 outstand- ing demolition orders for Palestin- an homes in East Jerusalem alone.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN A HOUSE IS DEMOLISHED?

Once a home is demolished, the family loses both the house as a financial asset and often the prop- erty inside it; in addition it is liable for the costs of the house demoli- tion which can run up to tens of thousands of dollars. To avoid these costs, Palestinians subject to ad- ministrative house demolitions may “opt” to undertake the demolition of their own home and pay a small- er fine in a deal with authorities.

It is not known how many Palestin- ians choose this route; however, ICAHD fears that their numbers rival those whose homes are de- olished by the authorities. The demolition of inhabited struc- tures may affect many families at a time. Often in the OPT, the entire extended family lives in close prox- imity to one another, and even in the same building. The demolition of one structure therefore, or col- lective demolitions within a defined area, can destroy not just the family domicile but also each nuclear family’s most immediate source of support and social capital. When a house is demolished, indi- viduals must cope with the trauma in an environment of family trauma, which makes it much more difficult to receive the needed care.

For hildren, who would normally be protected and cared for by their parents, the initial trauma is magni- fied. Depression, for instance, is one prevalent symptom after the ex- perience of trauma, especially one of loss. One study published on the psychological impact of house demolition showed a tendency among mothers in these families to develop symptoms of depression. Other studies have discussed the impact on children of parental de- pression. They show that children tend to experience behavioural and emotional disturbances 30 when parents are not able to meet the children’s needs due to distraction with their own.

HOW DO HOUSE DEMOLITIONS IMPACT COMMUNITIES?

House demolitions frequently impact Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, as well as other protected groups. Palestin- ian refugees comprise the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee case in the world today. In 2007, there were an estimated seven million Palestinian refugees worldwide and 450,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Israel and the OPT. The rights of Palestinian refugees and IDPs are guaranteed under international human rights and hu- manitarian law, which includes the Fourth Geneva Convention, the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, UN General Assem- bly Resolution 194, and UN Secu- rity Council Resolution 237.

COMMUNITIES AT RISK

In 2008, UN agencies confirmed that 198 communities in the OPT currently face forced displace- ment because of their proximity to settlements or their locations within so-called closed military zones. This includes 81 communities of 260,000 Palestinians and semi-nomadic Bedouin living between the Wall (a series of cement walls, barbed wire and “smart” fencing being con- structed in the West Bank by Israel) and the 1948 “Green Line” that demarcates the boundary between Israel and the OPT.

Ma’an Develop- ment Centre has also identified an additional 98 enclaves or areas in the West Bank where communities are surrounded by the Wall and settlements, or other Israeli infra- structure, in a manner that restricts Palestinian movement. The 312,810 Palestinians living in these enclaves are particularly vulnerable to inter- nal displacement, in part because they are more likely to have their homes demolished.

The 1993 Oslo agreements signed between Israel and Palestinians designated 60 percent of the West Bank as Area C, which falls under Israeli civil and security control. Over 94% of applications for build- ng permits in Palestinian commu- nities located in these areas were denied by Israeli authorities be- tween January 2000 and Septem- ber 2007. (Prior to the late-1970s when Israel began its settlement enterprise in the OPT, permits to build were readily granted to Palestinians. )

Building continues “In September 2007 the Special Rapporteur visited Al Hadidiya in the Jordan Val- ley where the structures of a Bedouin community of some 200 families, comprising 6,000 people, living near to the Jewish settlement of Roi, were demol- ished by the IDF. This brought back memories of the practice in apartheid South Africa of egardless, as Palestinians try to meet their housing needs; between January 2000 and September 2007, 5,000 demolition orders were issued and over 1,600 Palestinian buildings were demolished.

In the Gaza Strip, the creation of a 500-metre to one-kilometre wide military ‘buffer zone’ along the Egyptian border has transformed former residential areas into mili- tary no-go zones. 34 Sixteen thou- sand people in the southern Gaza Strip town of Rafah—more than 10 percent of its population—had lost their homes by 2004. 35 In June 2006, as many as 5,100 Palestin- ians were displaced in a series of Israeli military incursions in the Gaza Strip.

THE BEDOUIN

While our report focuses on the OPT, studies of house demolitions in the Negev reflect similar impacts on children. “House demolition is a traumatic and difficult event for all the members of the family,” said Alean al-Krenawi in an opinion written for Physicians for Human Rights. “The existence of the home fills a vital and basic need for chil- dren, and its absence impairs the development of safe and adaptive relationships. ” Bedouin who were displaced to he West Bank face a similar dilem- ma.

It is estimated that there are 6,000 Bedouin families in the West Bank. As Israel expands strategic settlements in the Jerusalem area, Bedouin living in open areas are increasingly vulnerable to demoli- tion orders and eviction. Moreover, when displaced, the Bedouin have limited coping resources. They are reliant upon herding with few opportunities for other income-raising activities. They have little social standing in an area where urban class structures dominate.

As a group on the margins now facing house demolition and evictions, the Bedouin represent the worst case scenario of house demolition and displacement. The Israeli policy of house demo- lition has had particular conse- quences for the Bedouin popula- tion inside Israel and the OPT. Tens of thousands of Bedouin, indig- enous Palestinian residents of the Negev (Naqab) before the state of Israel was created, live in com- munities unrecognized by Israel. Nearly 40 percent of the residents of the unrecognized villages in the Negev are under the age of nine. Construction in these villages is prohibited.

As a result, 45,000 tructures have been built ‘illegally’ in southern Israel, according to the Israeli Ministry of Interior, and could be ordered demolished. The escalating practice of demolishing destroying black villages (termed “black spots”) that were too close to white residents. Article 53 of the Fourth Geneva Convention prohibits the destruction of personal property ‘except where such destruction is rendered absolutely neces- sary by military operations’. ” —The UN Special Rap- porteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestin- ian territories occupied since 1967, 21 January 2008.

RELATED INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN AND HUMAN RIGHTS LAW

Fourth Geneva Convention Article 53 Any destruction by the Occupying Power of real or personal property belonging individually or collectively to private persons, or to the State, or to other public authorities, or to social or cooperative organizations, is pro- hibited, except where such destruction is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations. No protected person may be punished for an offence he or she has not personally committed.

Collective penal- ties and likewise all measures of intimidation or of terrorism are prohibited; Pillage is prohibited; Reprisals against rotected persons and their property are prohibited. Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement 1. Every human being shall have the right to be protected against being arbitrarily displaced from his or her home or place of habitual residence. 2. The prohibition of arbitrary displacement includes displacement:

When it is based on policies of apartheid, “ethnic cleansing” or similar practices aimed at/or resulting in altering the ethnic, religious or racial composition of the affected population;

- In situations of armed conflict, unless the security of the civilians involved or imperative military reasons so demand;

- In cases of large-scale development projects, which are not justified by compelling and overriding public interests;

- In cases of disasters, unless the safety and health of those affected requires their evacuation;

- When it is used as a collective punishment.