Globalization is only making this characteristic more noticeable, reproblematising already dense relation of individuality and universality, a defining character of the new global pattern of social forces.

While assessing UK urban development, globalization has instructed in anything, it is definitely an appreciation of the shift from an overly categorical perception of collective action to one that is more open-ended and reliant upon external factors as a recursive feature of structuration for interior scales. The cause-effect paradigms of local/global interrelations have mostly been discounted for a dialectical, relational model of exchanges, problematising the way globalize forces us to change basic sociological constructs such as community, culture, the nation-state, and their asymmetric relations of power and authority. From a theoretical viewpoint, broader-ranged movements have long harbored in Britain, at their core, a global aspect linking movement actors within different national contexts to other combined actors. The bridge between general social movements and their global strategies, while of interest and still mainly unexplored in the literature, has been much better recognized than localized forms of action within a globalize context.

The urban world of UK is distinguishing in socio-economic as well as in spatial terms like other developed country urban world. In spite of the infinite and intricate variations of tradition and culture that subsist within and between nations, cities appear to have, and to be acquiring, more in general than they have differences. UK cities have numerous similarities of physical appearance, economic structure and social organization and are inundated by the same problems of employment, housing, health, transport and environmental quality. Basically, globalization has almost the similar impact in numerous urban skylines, as commercial and residential areas are more and more subjugated by high-rise developments constructed in global styles. Streetscapes across the world are adjusting in the same way to hold the needs of the ubiquitous car, so cities are fast losing their individual layouts and architectural identities. Within buildings, workers do the same sorts of jobs, often on the same makes of computer or machine, and manufacture goods and services to the rations of world markets subjugated by a small number of global producers. Patterns of demand are converging as consumerism absorbs ever more of the world’s population. There are few cities where McDonald’s hamburgers, Fuji films, Microsoft’s Office and Coca-Cola are not eagerly available and purchased in quantity. Some of these similarities are superficial and hide significant underlying cultural differences, but the underlying trend is clear. There is escalating convergence among cities in physical and economic terms.

In UK, many urban residents live their lives in generally similar ways, with common concerns over home, children, school and work. Attitudes and expectations are shared as numerous aspire towards the lifestyles that are popularized and promoted by the mass media. Billions of people feast nightly on a diet of televised soap operas and international sporting events, with pop singers, film stars, sports personalities and media celebrities enjoying a worldwide acknowledgment and following. Identification is reflected in fashions and accessories, with designer brands and labels such as Adidas, Tommy Hilfiger, Calvin Klein, Levi, Nike and Nokia commanding widespread following. Such interests, fads and tastes are more and more independent of ethnicity, color, class and creed. They draw together and fuse what geography and culture traditionally separate and divide. The modern urban world is more than a motley assemblage of diverse settlements. Many observers argue that it is gradually becoming a unitary and uniform place, a global city in which most of its inhabitants are permeated with a similar set of all-inclusive urban attitudes and values and follow common modes of behavior.

Though, Great Britain was the first country to experience urban growth and urbanization as a consequence of industrialization. The industrial revolution, which began in the last third of the eighteenth century, malformed the country from a rural agricultural to an urban industrial economy in less than 100 years. The pace of population growth was unprecedented and unparalleled. At the first census in 1801 the total population of England and Wales was some 8.9 million. By 1891, the last census of the century, it had risen to 29 million, an increase of 326 per cent. The urban population grew by 946 per cent. Between 1801 and 1851 cities accounted for two-thirds of the population increase of 9 million people in England and Wales. A population that was 26 per cent urban in 1801 was 45 per cent urban in 1851. By 1861, for the first time in any country, more people in England and Wales lived in towns and cities than lived in rural areas (Jacobs, B.D. 1992: 72).

Industrial capitalism created a new guide of urban settlement in Britain termed by one contemporary observer ‘the age of great cities’. At the start of the nineteenth century, London, with some 861,000 people, was the largest city in the world, exceeding Constantinople (570,000) and Paris (547,000), but it was the only place in Great Britain with over 100,000 people. By 1851 its population had risen to 2.4 million and there were two other British cities, Liverpool and Manchester, with over 300,000. Birmingham, Leeds, Bristol, Sheffield and Bradford had between 100,000 and 300,000 and there were a further 53 cities between 10,000 and 100,000 in size (Leyshon, A. and Thrift, N. 1997: 54).

Britain was an urban industrial society for three-quarters of a century before any territory in what is at present the developing world passed the 50 per cent urban threshold, and the urbanization of most of the developing world did not gather real momentum until after 1950. It is significant, however, to place urbanization in its context of space and time. Global urbanization involves massive shifts in the distribution of population over a wide area and is intrinsically a slow process. It is perhaps no accident that self-sustaining urban development first occurred in Great Britain, a very small country, where forces of urban growth and urbanization were concentrated (Carter and Lewis, 1991). A sense of viewpoint is also important. When looking back over the last two centuries from the present, lags of a few decades appear to be of major implication In the context of eight millennia of urban history they are trivial.

A significant corollary of contemporary urban growth at the global scale is the rapid increase in the number and size of the largest cities. Against the background of a general rise in the number of people who live in urban places it are the metropolitan centers that are thriving and growing the fastest. United Nations estimates indicate that the number of cities with over eight million people increased from ten in 1970 to 24 in 2000. The number and size of mega-cities are increasing most rapidly in developing countries. In 1950, the only mega-cities, London and New York, were both in the developed world, while 18 of the 24 mega-cities in 2000 were in the developed world.

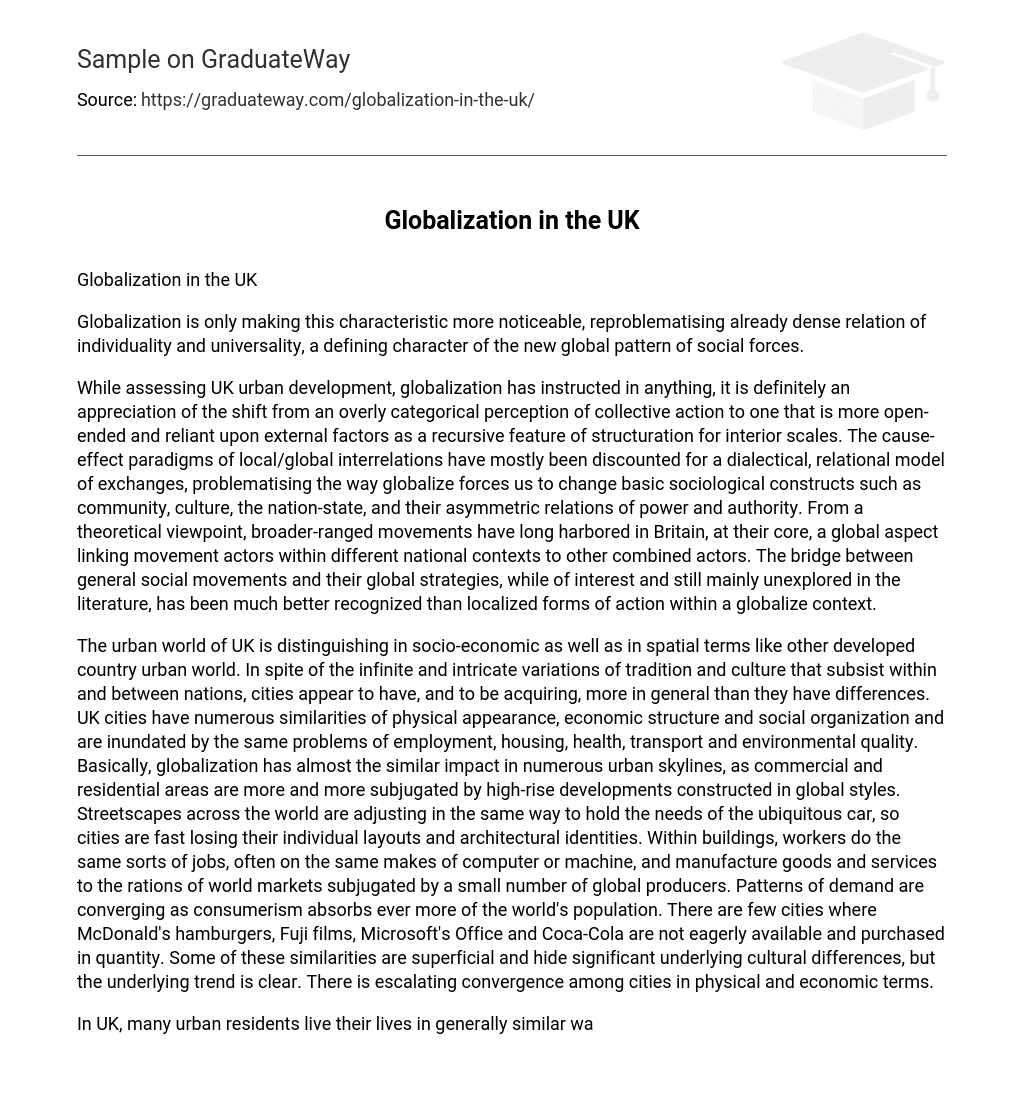

Table 1.1 UK cities: population change, 1991-2001

City

Population 2001 (000s)

Change 1991-2001 (000s)

Percentage

London

7,172

282

4.1

Birmingham

977

?29

?2.9

Leeds

715

?2

?0.3

Glasgow

578

?76

?11.6

Sheffield

513

?16

?3.0

Bradford

467

?8

?1.6

Edinburgh

448

27

6.3

Liverpool

440

?41

?8.6

Manchester

392

?46

?10.4

Bristol

381

?16

?4.1

Cardiff

305

5

1.8

Coventry

300

?5

?1.6

Sunderland

281

?16

?5.3

Nottingham

267

?14

?4.9

Newcastle

260

?19

?6.7

Source: 2001 Census.

In Britain, Globalization has impacted on the urban arena of identity formation, trashing taken-for-granted place-oriented associations. Appadurai contrasts his idea of flows and scapes with the notion of moderately stable communities from which people act. But have these communities already been transfigured? As Martin Albrow (1997) has forcefully argued in reply to Appadurai, the postulation of relatively stable communities in a framework of disconnected flows is highly problematic given the perspectives from which people view their actions, rendering community an open question in the age of global restructuring.

The interface of globalization and local struggles for democracy in Britain has created a lag between the edifice of a social practice and its embeddings in institutions. Globalisation has become, in this regard, a motor force for disjunctives between the personal, local, regional, national and international, depicting all these contexts flexible in terms of their economies of scale, and uncertain in terms of their chosen political alliances in stratified fields not yet fully institutionalized in the normative or regulative sense of the term. Urban social movements are the main conduit for the arbitrariness between local action and global accountability. And globalization as a form of collective action, whether we recognize it in terms of global consciousness, or systemic global relations, or the global interactivity of world spaces (Harvey 1973; Hannerz 1997), is first and foremost about the situatedness of shifting homes and new institutional homes. By situatedness we mean the capability of social actors, embarking on forms of communal action, to collocate by conveying an expressed structural and relational place to their action. This brings to the fore the problem of inserting action in a global world largely stripped of traditional markers, underscoring the present late modern context of detraditionalisation.

Moreover, the phenomenon of globalization has never been as obvious or transparent as in the procedure of economic globalization. Globalization as a concept has its roots in the bundle and bustle of financial markets as they rush to mobilize capital with its associated effects on national, regional and local economies. In this course of development, the economies of cities have emerged as a new field of inquiry from an urban social movement perspective. Britain city has become a prime site for fiscal disagreements stemming from higher levels of the state, as well as concerted action by grassroots groups targeting the local economy as part of their field of action. At the same time, the city has been theorized more and more in relation to global economic flows, suggesting a new direction in the way we recognize the expanding parameters of the new economy.

Though, the intensifying globalization of the last decades has transformed several social and economic structures, amongst them the hierarchy of cities. The new urban hierarchy, which has been emerging on a global scale, implies a sharper delineation of urban functions and has led to stronger differences between cities located on diverse hierarchical levels in terms of living conditions, conflict structures and development options than those prevailing during the Fordist era. Thus, urbanization patterns at the top of the hierarchy, in the so-called ‘global cities’, differ structurally from those of medium-sized and smaller cities or from cities less incorporated into global processes. But not only the cities at the top of the hierarchy are gradually more shaped by intensifying transnational links and flows, leading to new forms of inequality as well as to new avenues for action. modern urban research has set out to analyze the emerging structural differences within the urban system, explaining them within a variety of diverse approaches-as a process of economic-functional hierarchisation (Hamnett, C. (1996:126); as an uneven clustering of different roles and functions within a transnational system (head-quarter city, innovation centre, module production and processing, Third World entrepôt, retirement site: Capello, R., Nijkamp, P. and Pepping, G. 1999 :258); or as polarization between the organizing nodes of the global economy and subordinate cities within a global urban network, as in the global city literature. While such work begins to permit us to identify unique and specific economic and spatial patterns within a new typology of cities, research on urban conflict and movements under these globalize conditions is as yet rather undeveloped.

Work Cited

Albrow, Martin. 1997. The Global Age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Appadurai, A. (1996) Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press.

Capello, R., Nijkamp, P. and Pepping, G. (1999) Sustainable Cities and Energy Policies, Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Carter, H. and Lewis, C.R. (1991) An Urban Geography of England and Wales in the Nineteenth Century, London: Arnold.

Hamnett, C. (1996) Why Sassen is wrong: a response to Burgers, Urban Studies 33, 107-10.

Hannerz, U. (1997) Scenarios for peripheral cultures, in King, A.D. (ed.) Culture, Globalisation and the World-System: Contemporary Conditions for the Representation of Identity, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 107-28.

Harvey, D.W. (1973) Social Justice and the City, London: Edward Arnold.

Harvey, D.W. (1973) Social Justice and the City, London: Edward Arnold.

Jacobs, B.D. (1992) Fractured Cities. Capitalism, Community and Empowerment in Britain and America , London: Routledge.

Johnston, R.J., Taylor, P.J. and Watts, M.J. (2002) Geographies of Global Change: Remapping the World, Oxford: Blackwell.

Leyshon, A. and Thrift, N. (1997) Money Space: Geographies of Monetary Transformation, London: Routledge.

;