Australian transformation from a penal colony into democratic communities by the mid nineteenth century

Before the arrival of European settlers, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples inhabited most areas of the Australian continent. Each people spoke one or more of hundreds of separate languages, with lifestyles and cultural traditions that differed according to the region in which they lived. Their complex social systems and highly developed traditions reflect a deep connection with the land and environment.

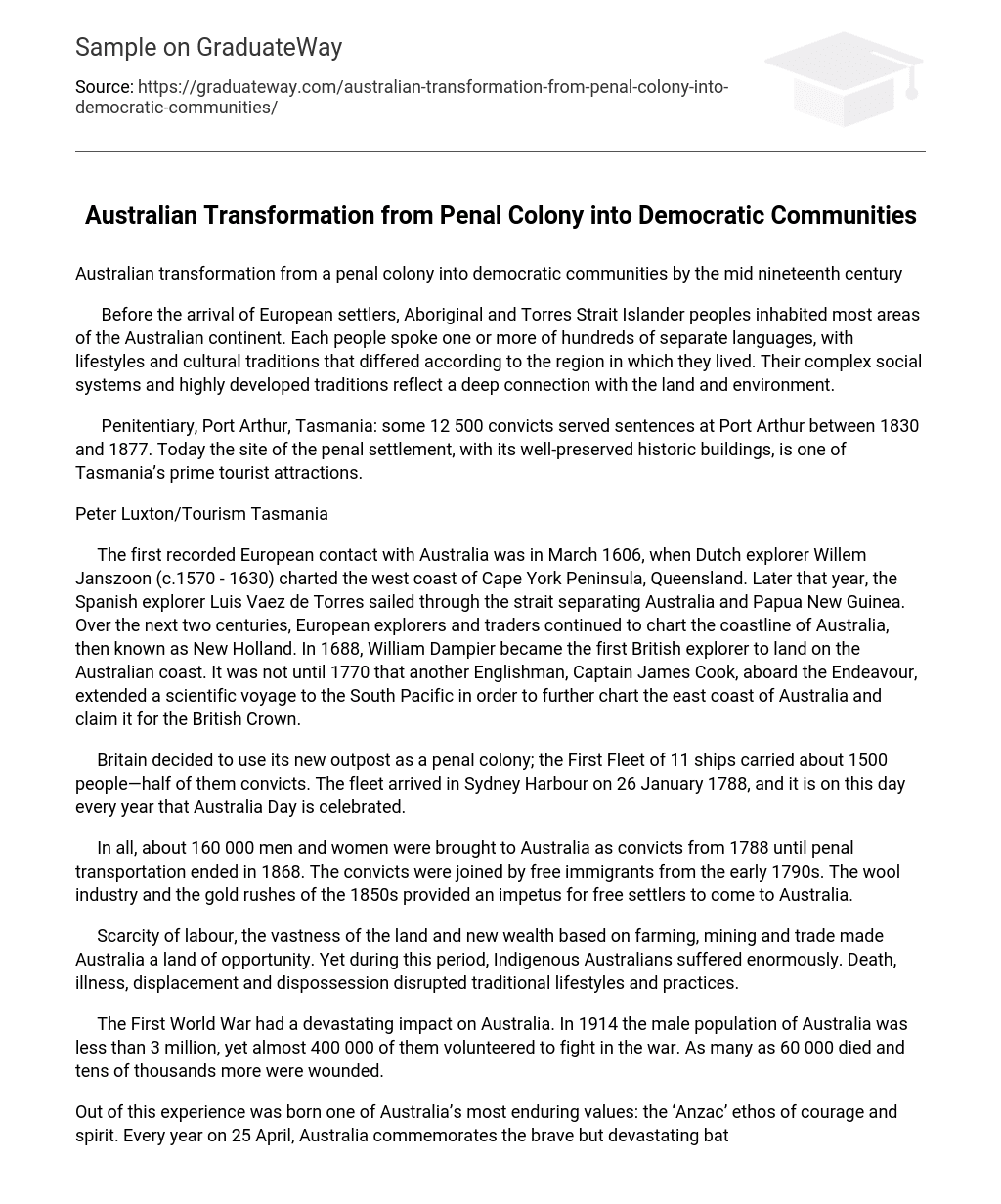

Penitentiary, Port Arthur, Tasmania: some 12 500 convicts served sentences at Port Arthur between 1830 and 1877. Today the site of the penal settlement, with its well-preserved historic buildings, is one of Tasmania’s prime tourist attractions.

Peter Luxton/Tourism Tasmania

The first recorded European contact with Australia was in March 1606, when Dutch explorer Willem Janszoon (c.1570 – 1630) charted the west coast of Cape York Peninsula, Queensland. Later that year, the Spanish explorer Luis Vaez de Torres sailed through the strait separating Australia and Papua New Guinea. Over the next two centuries, European explorers and traders continued to chart the coastline of Australia, then known as New Holland. In 1688, William Dampier became the first British explorer to land on the Australian coast. It was not until 1770 that another Englishman, Captain James Cook, aboard the Endeavour, extended a scientific voyage to the South Pacific in order to further chart the east coast of Australia and claim it for the British Crown.

Britain decided to use its new outpost as a penal colony; the First Fleet of 11 ships carried about 1500 people—half of them convicts. The fleet arrived in Sydney Harbour on 26 January 1788, and it is on this day every year that Australia Day is celebrated.

In all, about 160 000 men and women were brought to Australia as convicts from 1788 until penal transportation ended in 1868. The convicts were joined by free immigrants from the early 1790s. The wool industry and the gold rushes of the 1850s provided an impetus for free settlers to come to Australia.

Scarcity of labour, the vastness of the land and new wealth based on farming, mining and trade made Australia a land of opportunity. Yet during this period, Indigenous Australians suffered enormously. Death, illness, displacement and dispossession disrupted traditional lifestyles and practices.

The First World War had a devastating impact on Australia. In 1914 the male population of Australia was less than 3 million, yet almost 400 000 of them volunteered to fight in the war. As many as 60 000 died and tens of thousands more were wounded.

Out of this experience was born one of Australia’s most enduring values: the ‘Anzac’ ethos of courage and spirit. Every year on 25 April, Australia commemorates the brave but devastating battle fought by the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps—Anzacs—at Gallipoli, Turkey, in 1915. The day also commemorates all Australian soldiers who have fought in wars since then.

‘In the end ANZAC stood and still stands for reckless valour in a good cause, for enterprise, resourcefulness, fidelity, comradeship and endurance that will never admit defeat.’

—Charles Bean, historian of the First World War

The Commonwealth of Australia was formed in 1901 through the federation of six states under a single constitution. The non-Indigenous population at the time of Federation was 3.8 million. Half of these lived in cities, three-quarters were born in Australia, and the majority were of English, Scottish or Irish descent.

The founders of the new nation believed they were creating something new and were concerned to avoid the pitfalls of the old world. They wanted Australia to be harmonious, united and egalitarian, and had progressive ideas about human rights, the observance of democratic procedures and the value of a secret ballot.

While one of the first acts of the new Commonwealth Parliament was to pass the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, which restricted migration to people of primarily European origin, this was dismantled after the Second World War. Today Australia has a global, non-discriminatory policy and is home to people from more than 200 countries.

From 1900 to 1914 great progress was made in developing Australia’s agricultural and manufacturing capacities, and in setting up institutions for government and social services.

The period between the two world wars was marked by instability. Social and economic divisions widened during the Depression years when many Australian financial institutions failed.

During the Second World War Australian forces made a significant contribution to the Allied victory in Europe and in Asia and the Pacific. The generation that fought in the war and survived came out of the war with a sense of pride in Australia’s capabilities.

After the war Australia entered a boom period. Millions of refugees and migrants arrived in Australia, many of them young people happy to embrace their new lives with energy and vigour. The number of Australians employed in the manufacturing industry had grown steadily since the beginning of the century. Many women who had taken over factory work while men were away at war were able to continue working in peacetime.

The economy developed strongly in the 1950s with major nation-building projects such as the Snowy Mountains Scheme, a hydro-electric power scheme located in Australia’s southern alps. Suburban Australia also prospered. The rate of home ownership rose dramatically from barely 40 per cent in 1947 to more than 70 per cent by 1960.

Other developments included the expansion of the social security net and the arrival of television. Melbourne hosted the Olympic Games of 1956, shining the international spotlight on Australia.

The 1960s was a period of change for Australia. The ethnic diversity produced by post-war immigration, the decline of the United Kingdom and the Vietnam War (to which Australia sent troops) all contributed to an atmosphere of political, economic and social change.

A new dimension to the meaning of citizenship was added in the late 19th century as feelings of an Australian nationalism began to intensify. As one commentator (Greenwood, 1955: 146) has noted, Australian nationalism contained a set of distinctive social values motivated by a belief in equality of opportunity, and a conviction that Australians had a right to the good life. This complex mix of ideas and emotions was partly an ‘apprehension of present reality, partly aspiration towards an ideal future in Australia.’ Republicanism, labourism, socialism and patriotism were all elements of this nationalist sentiment and were part of a further stage in the evolution of Australian democracy towards a federal system of government.

The movement for federation was prompted by a growing awareness of the common problems that confronted most of the colonies. These included ‘external’ problems of immigration and defence as well as ‘internal’ or interstate issues concerning transport, communications, free trade and labour. A core motivation of the movement was that a national government could best deal with such problems. The possibility of federation raised the institutional problem of the possible division of powers between the federal government and those of the states. A ‘unitary’ system, like that operating out of Westminster in Great Britain, with power concentrated in a central, national government, held no appeal to a collection of independent colonies. The colonies were only interested in handing over a limited set of their powers to a national government, while retaining extensive power for themselves.

The first official intercolonial conference (the National Australasian Convention) to give detailed attention to creating a possible federation of the Australian colonies was held in Sydney during March and April 1891. Henry Parkes, the Premier of New South Wales, was made the president of the convention. The relative powers to be given to the two Houses of the new Federal parliament was a major point of contention. In addition to the enumeration of separate powers for states and Commonwealth, those favouring states rights argued in support of a bicameral parliament, comprising a House of Representatives and a Senate in which the latter would be given sufficient constitutional power to protect the interests of the states. Supporters of the Westminster model of responsible government favoured a strong House of Representatives with significantly greater powers than the Senate. Supporters of states rights, which were in some cases also the rights of minorities, wanted a Senate with equal, or almost equal power to the House of Representatives. A federation in which powers would be shared between a federal government and a series of state governments became the preferred model. The following extract indicates the kinds of issues at stake in the debates of the time.

Sources

Alan Atkinson. 2004. The Europeans in Australia, Vol.2 Oxford University Press Melbourne

Anne Coote. 1999. ‘Imagining a Colonial Nation: The Development of Popular Concepts of Sovereignty and Nation in New South Wales’, Journal of Australian Colonial History, Vol.1

DWA Baker. 1985. Days of Wrath, a life of John Dunmore Lang, Melbourne University Press Melbourne

Graeme Aplin (ed.). 1988. A Difficult infant: Sydney before Macquarie, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington

Peter Cochrane. 2006. Colonial Ambition, Foundations of Australian Democracy, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne