As described in the previous installment of this series, the fiercely independent and often predatory Cossacks were a thorn in the side of a good many rulers, from Poland to Russia to the Turkish Empire. Being fighters without equal, though, they were useful to have on one’s side in wartime. The trouble was getting them to accept any discipline but that of their own leaders.

When the Livonian War broke out in 1558, with Russia facing off against Poland-Lithuania and various other foes including Sweden, the Voivode of Kiev and the Major of Cherkasy both recruited Cossacks into their armies. Registered, official Cossack subjects of Poland-Lithuania were created for the first time in 1572 by King Sigismund II. They were the only Cossack military formations recognized by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Among the earliest reforms of Cossack units was that attempted by Stephen Bathory, King of Poland (closely related to the notoriously sadistic Blood Countess, Elizabeth Bathory). The Cossacks were waging war as they pleased against Moldavia, Wallachia and other provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Stephen Bathory had made an expedient treaty with the Ottoman Sultan, so he sent a representative to look into the Cossack raids and ordered all local officials to co-operate fully with him. A particularly wild Zaporizhian leader, Ivan Pidkova, had recently overthrown the Hospadar of Moldavia, a puppet of the Sultan’s.

The nickname Pidkova means “horseshoe”. It was said that he would ride his stallions until their horseshoes broke. The surviving portrait of him matches the legendary Cossack image, with a tough aggressive expression, scalp-lock and flowing moustaches. He was possibly the first hetman of Ukrainian Cossacks to have been elected by overwhelming vote of the entire Zaporizhian Sich. His territory was close to Moldavia, and he claimed to belong by blood to the Moldavian ruling family. Thus he assumed the right to buy into their family quarrels. He had chased the Hospadar of Moldavia from his throne and he resisted the Turkish reaction successfully – for a time. Turkish forces, with the help of their ally Stephen Bathory, defeated him and took him captive at last. He was beheaded in Lviv, where a memorial to him exists today, featuring his fierce bust and a horse-shoe below it.

Yes, REH could have written a story about Ivan. The Don Cossack community had arisen at least as early as the Zaporizhians, on the vast steppes around the lower reaches of the river. They too originated among outlaws and runaway serfs. Cossacks of Ryazan were defending Russia against the Golden Horde as early as the mid-fifteenth century.

REH’s poem “A Song of the Don Cossacks” might be referring to those very events.

Gray light glances

Along our lances –

Both of us sons of our Volga mother.

Kites shall feast when ranks burst asunder

And the roar of the red tide hurls us under.

When the white steel glints and the red blood spurts –

Death in the camps and death in the yurts.

When the crimson shadows of twilight fall

We shall be feasts for the white jackal.

Wolf-lover, wolf-brother,

We be sons of the self-same mother,

Though between us flows a red-stained tide.

Horse and man,

Ride we far,

You for the Khan,

I for the Czar,

Wolf-lover, Tartar-brother, ride!

In Ivan the Terrible’s reign, the legendary Don Cossack warrior Yermak Timofeyevich headed an expedition to conquer Siberia. Historians are divided as to whether Yermak led his Cossacks eastward as a hireling of the great merchant family, the Stroganovs, or whether it was his own idea and they grabbed credit in Russia afterwards. Still, he set out in 1582 with about eight hundred and fifty men. Their journey was epic. They navigated down rivers in high-sided boats, crossed the Ural Mountains on foot, then took the capital of the Sibir Khanate without losing a man of their own forces. Yermak gained the allegiance of the Ostyak tribe and subdued others through 1584, though his army had been reduced to 300 men by that time. His achievements ended when he was drowned in his armor during an ambush, attempting to gain supplies to feed his starving men. He hadn’t completed the conquest of Siberia, but he had removed the last great obstacle and made an impressive beginning.

Another famous Cossack leader was Bohdan Khmelnitsky. When he inherited his father’s estates, the Polish king confirmed his rights to them and everything should have gone smoothly. However, a bunch of lawless magnates forced him out, seizing his lands. The Polish king found it expedient to ignore their actions, for all Khmelnitsky’s protests.

Bohdan raised a revolt among the Cossack regiments and the Zaporizhians, in 1647. The rebels demanded that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth restore the Cossacks’ ancient rights and curtail the Greek Catholic Church in the Ukraine. Khmelnitsky met an army under Stefan Potocki in May, 1648, and handed the Poles a crushing defeat, swiftly followed by another Cossack victory at Korsun. He persuaded many “registered” Cossacks to switch sides, and even turned the Crimean Khanate into an ally. At Christmas, 1648, he entered Kiev in triumph.

Lack of international support and his own failing health brought Khmelnitsky down in the end. In mid-1656 a cerebral hemorrhage left him paralyzed. Only days afterwards he died. His revolt was the subject of one of Poland’s most popular novels ever – With Fire and Sword, by Sienkiwicz (1884). It was published in English translation in Boston in 1904.

The Cossacks remained as fiercely independent as ever. They inflicted a severe defeat on Turkish forces in 1675, but nevertheless the then Turkish Sultan, Mehmed IV, dispatched a letter to them calling upon them to submit to his rule. It opened with the usual honors and claims.

Sultan; Son of Muhammad; brother to the sun and moon; grandson and viceroy of God … emperor of emperors; sovereign of sovereigns; extraordinary knight, never defeated … etcetera.

The Cossacks, under their leader Ivan Sirko, prepared a letter in response.

“Thou Turkish Satan, brother and companion to the accursed Devil … Greetings!” it begins.

And continues:

What the hell kind of noble knight art thou, that cannot even slay a hedgehog with thy bare arse? The Devil defecates, and thy army devours the result! … thy army we fear not, and by land and on sea we will do battle against thee.

Thou scullion of Babylon … thou beer-brewer of Jerusalem, thou goat-flayer of Alexandria, thou swineherd of Egypt, both the Greater and the Lesser … thou grandson of the Devil himself, thou great silly oaf of all the world … a blockhead, a swine’s snout, a mare’s (censored), a slaughterhouse cur, an unbaptized brow! The Devil take thee! That is what the Cossacks say to thee, thou basest-born of runts! Unfit art thou to lord it over true Christians!

The date we write not for no calendar have we got; the moon is in the sky, the year is in a book, the day is the same with us here as with thee over there, and thou canst kiss us thou knowest where!

Nothing mealy-mouthed or ambiguous there.

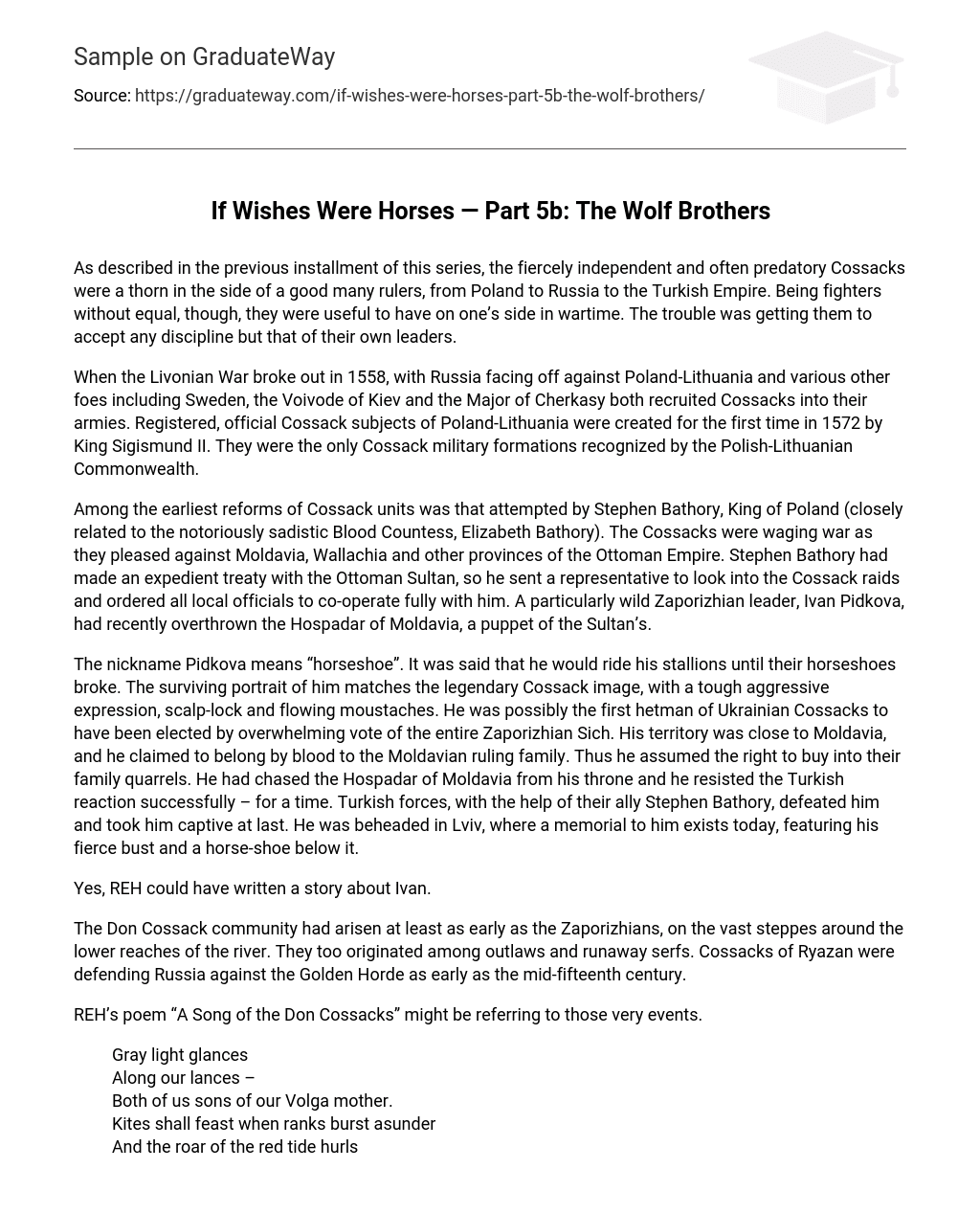

Russian artist Ilya Repin began the painting that immortalizes the scene in 1880, which appears at the top of this post. He finished it in 1891. Almost seven feet by twelve, Reply of the Zaporizian Cossacks shows the horde of jolly roughnecks gathered around a scribe at a table, communally dictating the letter and rocking with laughter at each new choice phrase they include.

Other Cossack communities included the Volga Host. Like the Don and Zaporizhian Hosts, it was formed from outlaws and runaway peasant serfs, but somewhat later, in the 16th century. They were chiefly Volga Cossacks who followed Yermak into Siberia. Cossacks who left the Volga Host and resettled on the Terek River (between 1575 and 1580) became the Terek Cossacks.

The central government never ceased its efforts to tame the Cossacks and make them servants of the state. By the late eighteenth century, with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Crimean Khanate much weakened, the Russian state had less use for the Zaporizhians as buffer warriors against these former powers, and found the Cossacks of the region a pest since they still formed a haven for runaway serfs and were chronic rebels besides.

The Empress Catherine the Great had them destroyed and scattered. Some fled to the Danube, while others joined the Russian army’s cavalry regiments. A mere decade later, with the Ottoman Empire becoming more actively hostile to Russia, the government saw its actions had possibly been hasty, and former Cossacks were gathered as the “Host of the Loyal Zaporizhians” in 1787. For their loyal and effective service in the Russo-Turkish War of 1787-92, they were granted lands east of the Sea of Azov as the “Black Sea Cossack Host”. Finally, in the mid-nineteenth century, they merged with the Azov Host, the Caucasus Host, and thousands of Cossacks returning from the Danube, to form the Kuban Cossack Host.

Wherever their masters lived and whatever name they took, the performance of the Cossack horses remained as impressive as ever. Regular Russian cavalry steeds were larger, but for endurance and agility the Cossack horse could still match any. Sir Robert Thomas Wilson, a distinguished English cavalry commander who was seconded to the Imperial Russian Army in 1812, wrote that the creature was a “very little but well bred horse, which can walk at a rate of five miles and hour with ease, or, in his speed, dispute the race with the swiftest.”

Russia, for centuries, had been a strictly conservative country, in religious and other matters. It had been isolated from currents of thought in Western Europe, and for the most part, its people were content with that, the aristocrats included. They might take interest in western ideas themselves, be interested in western music, theatre, and even science, but the last thing they desired was to have their underlings getting modern ideas. Peter I the Great, who ruled Russia in the first quarter of the eighteenth century, was the first Tsar who took major measures to bring the government into the modern world and introduce western technology. (Ivan the Terrible had taken a few steps in that direction in his early years, his “good years” – before he became as violent and unstable as a grenade with a loose pin.)

Introducing foreign strains into Russian horse breeding – except for Turkoman and Arabian horses – had been occasional and inconsistent too. The first private stud farms dedicated to breeding Don Horses did not appear until the end of the eighteenth century, when Bonaparte was rising to power in France. At Austerlitz in 1805, with fewer than 70,000 troops, he defeated 90,000 Russians and Austrians – but there, many Cossacks were fighting on foot due to a shortage of horses. During Bonaparte’s invasion of Russia, the most effective resistance and deadly harassment of his Grand Army was performed by mounted Cossacks.

In 1814, after Napoleon’s defeat (he tried a comeback in 1815, but we know how that turned out), a huge force of Cossacks under their Ataman, Count Matvei Platov, entered Paris – sixty thousand of them. Each man had two horses of the redoubtable Don breed, and they left a lasting impression. By 1850 stud farms were producing Don Horses as remounts for the entire Russian army, not the Cossack regiments alone. They bred for the characteristic agility, stamina and tough hoofs, but also for greater height and the typical chestnut coat with a golden sheen. The French and other foreign nations remembered them, so the demand abroad grew, and many Don Horses were exported, mainly through Hungary.

The nineteenth-century studs blended the Don Horses with other breeds, though often they were closely related. Arab horses may originally have been partly developed from the Karabakh beasts of the Caucasus. During the Arab invasions of the 8th and 9th centuries, many thousands of Karabakh horses had been taken by the conquerors, and Karabakhs, like Don Horses, are known for endurance and loyalty, as well as a characteristic golden chestnut hue.

In 1836 the heir of the Russian general Madatov sold his entire stable, among them two hundred Karabakh mares, to a horse-breeder in the Don region. These Karabakhs were used for improving the modern Don Horses into the 20th century. Khan, a Karabakh stallion, won a silver medal at an international horse show in Paris in 1867. Karabakhs were popular throughout Europe – including England – during the 1800s. Besides Karabakhs, Don mares were bred to Orlov trotters, a breed created by crossing English and Dutch mares with Arabian stallions. Orlovs are handsome and elegant, but hardy, swift and good workers, though their color is generally grey. Costly, they were mostly employed by nobles for riding and harness racing. They could move at an outstandingly fast trot.

With World War One, and the transformation of war by barbed wire, tanks and machine guns, the cavalry saw its last days, even in conservative Russia. The revolution of 1917 took Russia out of the war against Germany, but the Russian Civil War which followed lasted from 1917 to 1920 and raged from the Ukraine to Siberia. About 15 million people lost their lives in it – as many as died in World War One.

The Cossacks, a folk which originated with runaway serfs and other rebels against the Tsars, by this time were among the Tsar’s most loyal supporters. By and large Cossacks fought consistently on the White side. They were among those who suffered most from the Red victory, many being sent to Siberian gulags and many more fleeing into exile. The old Cossack who reminisced in tears about his people’s horses to Rabbi Futerfass in the prison camp (see previous post) was one of many thousands.

The Cossacks’ cherished horses also suffered appallingly. The equine population of Russia had been 35 million in 1916. By 1920 it had dropped to 24 million. Cossack men and horses alike might have endorsed REH’s lines of poetry:

Towers reel as they burst asunder,

Streets run red in the butchered town;

Standards fall and the lines go under

And the iron horsemen ride me down.

Out of the strangling dust around me

Let me ride for my hour is nigh,

From the walls that prison, the hoofs that ground me,

To the sun and the desert wind to die.